To Be, or Not to Be in Japan, That is the Problem

Consider involving Japan in your drug development program, and start thinking about it now

Globalization in the pharmaceutical industry is an ongoing and never ending process due to the monotonically increasing desire of people all over the world to gain faster access to healthcare innovation, fueled by the tireless efforts of the drug manufacturers to make that happen. Due to the nature of pharmaceutical products’ property largely consisting of functional value (i.e., you purchase the product because of the disease-treating function of it and not because of other non-functional value such as corporate brand), demand for such products should not be different among patients in different countries. That is, despite possible minor variations in the genetic makeup of patients from different countries, the assumption that drugs that work for a patient living in one country should work for those in another still holds. Therefore, pharmaceuticals generally qualify to become global products with a larger commercial potential. In other words, you are foregoing the market opportunity if you do not reach out to all the geographical markets with your new product.

Globalization in the pharmaceutical industry is an ongoing and never ending process due to the monotonically increasing desire of people all over the world to gain faster access to healthcare innovation, fueled by the tireless efforts of the drug manufacturers to make that happen. Due to the nature of pharmaceutical products’ property largely consisting of functional value (i.e., you purchase the product because of the disease-treating function of it and not because of other non-functional value such as corporate brand), demand for such products should not be different among patients in different countries. That is, despite possible minor variations in the genetic makeup of patients from different countries, the assumption that drugs that work for a patient living in one country should work for those in another still holds. Therefore, pharmaceuticals generally qualify to become global products with a larger commercial potential. In other words, you are foregoing the market opportunity if you do not reach out to all the geographical markets with your new product.

Yet there are hurdles in every market which will prevent faster transfer of technology and/or transportation of pharmaceutical products to their respective countries. The most notable among such hurdles are regulatory requirements. While all countries’ governments owe the same responsibility to offer safe and efficacious drugs to their nationals, countries have different levels of rigor in trying to investigate whether those such drugs are equipped with the right evidence to support the regulatory approval. Some countries only ask for documents in order to approve a drug in their markets, while Japan is among the most rigorous countries which requires local clinical trials for the product to be approved for commercialization in its market.

This seemingly meticulous process requires careful preparation and reasonable cost. So, the manager responsible for planning to develop a pharmaceutical product, whether he/she is with a large multinational corporation or a relatively small biotech, will have to decide whether she/he wants to go to Japan sooner or later. And if the answer is the former, i.e., her/his company is aiming to launch the product simultaneously with the Western market, the way to go is without doubt involving Japan in the pivotal global trial. Therefore the choice will be, whether you want to recruit patients from Japan in one of your phase 3s or you want to carry out a Japan-stand alone development plan. In spite of the paperwork and some additional cost associated with the process, our recommendation is to consider involving Japan as early as possible. Here’s why.

Commercial Opportunity

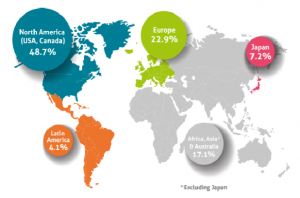

While Japan is giving out its share due to the faster growth of US and China, it is still the third largest country market holding 7.2% of the global pharmaceutical sales[1]. Apart from its size, the Japanese market has some unique features that will make it attractive for drug manufacturers.

Source: EFPIA “the Pharmaceutical Market in Figures 2019”

Market Access

The National Health Insurance system covers all Japanese citizens with uniform benefit plans nationwide. All citizens will have equal and immediate access to healthcare services based on the clinical demand. This principle is reflected in the process of determining the list prices of new products, or enlistment to the NHI price list. Once a product is granted regulatory approval, the enlistment will happen in 60 days in general, and no later than 90 days after the date of approval. Thereafter, the product will become fully accessible nationwide from the very beginning. Compared to other social health insurance systems, which manufacturers will have to go through time consuming negotiations with the payer(s), this is a fairly straightforward process. Manufacturers will be able to monetize their innovation early and sizably, which is good news not only for them but also for their investors.

Price Advantage

In addition to this, there are considerable advantages in the pricing process. If competitors are also arriving in the market, the earlier you launch the product the better your product will benefit. Followers launching after more than three years of the first-in-class approval or becoming the 4th or later product to launch in the same category of drugs could be priced at a disadvantage, which suggests that if you beat your comps by three years you may hurt them quite significantly.

Cost Saving

Clinical trials are associated with a significant cost, and recruiting Japanese subjects in addition to the already planned global phase 3 is seemingly just making the situation worse. However, given that the product is anyhow going to approach Japan later (it will be difficult to justify not doing so, especially to your shareholders), it is reasonable to include Japan in the global pivotal trial rather than to do a stand alone study. This is simply because PMDA, the Japanese regulatory authorities, does not require the Japan portion in a global trial to reach statistical significance on its own (of course, this is the reason why you do a global trial at all), but it will ask for such data in a standalone study. A good example is the first two ALK inhibitors, Xalcori and Alecensa, for the treatment of ALK+ NSCLC. In its pivotal trial, Xalcori carried out a global study which enrolled 136 subjects, but among them only 6 were from Japan[2]. Alecensa on the other hand, according to its clinical data package[3], carried out a Japan standalone trial enrolling 46 subjects in the pivotal phase II segment. It could have been a strategic decision for either Pfizer or Chugai to carry out different development pathways, but it is a no-brainer that including Japan in the global plan is more cost effective than to approach it separately.

Risk Reduction

Avoiding duplicative trials is not just a matter of cost, but there is always a small possibility of flunking the test. Also, if the plan is to approach the Japanese market separately in a later time, competition may become fiercer and you may be forced to achieve more challenging goals, which may further increase the probability of failure. One example is Zemplar, a treatment for secondary hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients. This product was first approved in 1998, but its development in Japan was as late as in the early 2010’s, and a similar product called Oxarol became the standard of care while Zemplar was absent. As a latecomer in the market, Zemplar had to show comparative data against the Oxarol, which is more difficult to prove than to show statistical significance against placebo. As it turned out, Zemplar failed to demonstrate non-inferiority against Oxarol[4], and the product is not yet approved in Japan as of 2021 (and most likely will never be). In this case, not only the product missed out on the Japanese market because it was late to come in, but it now has an everlasting scar on its record which may affect its reputation in other markets.

Be Prepared

Of course, it is not the case that the development program could instantaneously involve Japan. Usually, at least the dosage of the active ingredient will need to be justified prior to the pivotal trial, and that will take a relatively small but independent study in Japanese subjects. However, this may not always be the case, particularly if the patient population in Japan is too small. The manufacturer definitely needs to discuss with the PMDA what should be the requirements for the product to be approved, and the earlier the better. Even if you don’t intend to disregard Japan, you might already be too late to recruit Japanese patients in your phase 3, if you don’t think about it now.

[1] https://efpia.eu/media/554521/efpia_pharmafigures_2020_web.pdf

[2] https://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/interview/2/672212_4291026M1023_2_1F.pdf

[3] https://chugai-pharm.jp/content/dam/chugai/product/alc/cap/if/doc/alc_if.pdf

[4] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1744-9987.12242